In addition, as part of my assignment to work with the teachers at Moroni High School, we have created a wiki site to compile the oral and written histories of many of the early pioneers of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints in Kiribati. The Church has only been in Kirbati since 1975, so many of the pioneers are still available to share their history with us. The site is will be continually updated, as other Kiribati church pioneers add their personal, school and church history to the site. The goal is to provide easy access for the public at one location - much of the early Church history of the saints in Kiribati. Hopefully, in the near future some video interviews will be added to the site. The wiki site is:

http://kiribati-lds-pioneers.wikispaces.com/

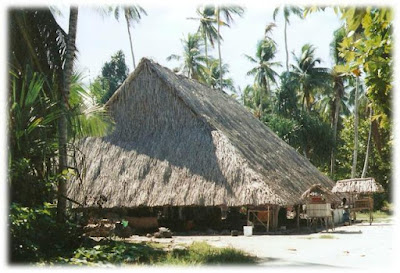

The Maneaba in Kiribati

There are two types of education for the I-Kiribati: Formal and Informal. Schools provide the formal education and families and extended families provide an informal education for their children, The informal education consists of learning the I-Kiribati traditional and material skills, which are passed down from generation to generation - - father to son and mother to daughter.

The village household is the most important unit, and within the village, the most important person is the unimane. He is the symbol of a traditional I-Kiribati, understood by the village people to be an elderly man who was usually not well educated in the modern sense but is normally a source of wisdom and pride in the community. He does not have to be physically involved in village projects. His role is that of a ceremonial figure as well as an executive in the management of community affair.

The traditional sanctity of the maneaba or meeting place and the authority of the unimane (old men) still pervade and dominate the Kiribati village community. Every village has at least one maneaba, which is used as a meeting place and to hold important social and cultural events. It is the largest building in a village, signifying its importance and central role in the I-Kiribati way of life.

Traditional Material Skills of I-Kiribati

Especially impressive, are the skills and techniques used by the unimane in constructing a Maneaba. He truly is a master craftsman. All the materials used in its construction are found in the immediate vicinity of a village - no nails, glue, metal brackets or other commercial made materials are used. There are no pre-made roof trusses, power tools, or modern devices.

All the building materials used are from coconut palm and pandanus trees. The wooden poles are from tree trunks, limbs and branches. The poles are lashed together using a series of complicated lashing knots and wooden pegs. The string (cordage) for the lashings is hand spun from coconut fibers. Some of the traditional skills and techniques required to build a Maneaba (sometimes spelled Mwaneaba) are described and shown in this post. A maneaba is the size of a large two story barn. Its steep pitched roof is shaped to resemble a bird in flight.

**Much of the information and photos were taken from a magazine article found in: Shima Journal: The International Journal of Research into Island Cultures.

Te Mwaneaba

Te mwaneaba (the traditional meeting-house) is central to social existence on the isolated coral atolls that form the Nation of Kiribati. It is a place of tradition and ritual, and has changed only slightly since the establishment of the original prototype maneaba of Tabontebike around 1650, on the island of Abaiang. In an maneaba the seating positions of the old men (unimwane) of the village demonstrate a hierarchy. The maneaba is also a place of formal village decision-making and for significant social and cultural events.

The construction and completion of a traditional mwaneaba requires the contributions of the whole village for string, thatch, tree-cutting, weaving and general labor. It draws upon many of the traditional and material skills associated with the culture of the I-Kiribati. The combined effort and experience of 'te mwaneaba' binds people together as a social unit. The maneaba architect and master builder is usually an old man (manwane) who has learned the trade through experience and from traditions passed down in his family. Traditionally, he is considered somewhat of a sorcerer, because building a maneaba requires invocations to the Anti (spirit), the observing of certain rites and following the rules, which he feels would be foolish to ignore.

The traditional mwaneaba is built primarily from pandanus and coconut palm trees.

In the whole of the construction there are no nails, screws or glue.

|

| Example of a complex knot used in constructing a maneaba |

The strength of the massive structure depends on wooden pins (pegs), well fitted joints and string, "te kora", made from coconut husk. The builders use sophisticated knots and lashing patterns. Lashings though out the maneaba are not random, but carefully specified for each joint. Many knots are highly complex and difficult to tie. A large part of a traditional builders skill is his knowledge of this critical part of the construction.

|

| Rolling Coconut fibers across thigh to make te kora (string) |

String (Cordage) The Production of string from the coconut husk is a painstaking process involving months of preparation. Husks are gathered, then buried in sand below the lagoon's tide line and covered with coral boulders. After about three months of soaking, the husks are removed and the fibrous inside teased out and dried.

|

| Coconut fiber string or cordage used to make a broom |

String making is a good example which illustrates the division of labor in I-Kiribati. Women make the flexible items, like Cordage (string), while the men work with the harder materials, such as wood. It appears that women are spinning string all the time. They produce so much that they often roll it into large balls and store it for later use. String is used in the construction of houses and maneabas, to make canoes, and small items such as belts and fishing nets. There is a continual need for cordage. Even though they could purchase machine-made nylon or cotton string and rope, the people of Kiribati prefer handmade cord. When tying canoe planks together, they use coconut fiber because it swells up and plugs the holes. It's cheap, strong and does its job very well, sometimes even better than the modern alternatives.

Only males build and repair the large structures, while the women weave mats and produce the string that binds everything together, each role is socially valued.

In this traditional division of labor, men, women and children have distinct responsibilities. Each task requires a traditional material skill that is socially recognised. Each skill provides a sense of worth and is valued by the village. Many I-Kiribati keep their skill a closely guarded secret for all but the most trusted family members. The skills have value for what they represent symbolically in relation to a person individuality and his or her cultural identity. The skills are passed from one generation to the next.

Only males build and repair the large structures, while the women weave mats and produce the string that binds everything together, each role is socially valued.

|

| Pandanus Tree - The leaves and Pronds are used for weaving mats and for thatch on roofs |

|

| Young girl learning the art of weaving mats |

In this traditional division of labor, men, women and children have distinct responsibilities. Each task requires a traditional material skill that is socially recognised. Each skill provides a sense of worth and is valued by the village. Many I-Kiribati keep their skill a closely guarded secret for all but the most trusted family members. The skills have value for what they represent symbolically in relation to a person individuality and his or her cultural identity. The skills are passed from one generation to the next.

Historically, the maneaba has been as much symbolic as functional. There are three basic types of traditional mwaneaba: Tabontebike, Tabiang and Maungatabu. The principal difference between each style is in the proportions (i.e., length to width) and details in the number and positioning of the supporting wooden beams. Generally, the gables of a mwaneaba face north and south with the west side facing the lagoon. The building of a maneaba commences with an unimwane, a senior man in the village, deciding upon its length. Most are approximately forty metres in length by twenty metres wide but some may be as much a sixty meter long and a proportional width. Clearly an intelligent and proud people had been responsible for this symmetry, the artistic arrangements of the beams and the skillful building.

The size of each maneaba is determined by such criteria as the likely number of people who will use it, the land available for its site and the construction style with which the builder is familiar. First, the length marking maneaba’s eastern side is staked out and divided into half, half again and half again (divided in eighths). Most of the key elements in maneaba will be positioned by divisions or multiplications of these units.

After the size and proportions have been established, coral supports, "boua", are placed in position and beams (tatanga), are placed horizontally upon them, forming low eaves (approximately 4 feet high). Then larger boutabu (poles) and smaller boua ni kaua posts are positioned vertically and temporarily held in place. The complex of horizontal and diagonal beams, "te bao ni moto, te bao, te kautoko and te taubuki" are then positioned and lashed into place.

After the size and proportions have been established, coral supports, "boua", are placed in position and beams (tatanga), are placed horizontally upon them, forming low eaves (approximately 4 feet high). Then larger boutabu (poles) and smaller boua ni kaua posts are positioned vertically and temporarily held in place. The complex of horizontal and diagonal beams, "te bao ni moto, te bao, te kautoko and te taubuki" are then positioned and lashed into place.

Positioning the ridge pole, te taubuki, requires great skill, strength and courage. Working at heights of 12 -13 metres, a small team of men balance on the beams of the west and east sides of te mwaneaba as they haul the ridgepole into place at top dead- centre. Diagonal roof beams, oka, are positioned and thinner slats of wood, kaukau and bwai ni kakori, are lashed across the oka to form a framework on which to attach the pandanus thatch, te rau. The thick thatch is attached to the roof and serves as a perfect barrier against the heat and the rain. The floor of the traditional mwaneaba is covered with fine smooth coral stones and overlaid with long lengths of coarsely woven palm fronds, inaai. The builders must climb a pole and work near the roof structure to lash horizontal and diagonal beams to the vertical ridge poles. This requires confidence, courage and skill as they do the lashing sometimes nearly 40 feet above the floor. Wooden pegs are often placed within a lashing to keep the knot from slipping or sliding. The inside of the maneaba has a cathedral like appearance.

Vertical poles lashed diagonally to cross beam

The maneaba comprises three significant areas: 1) the marae, which surrounds the building and is covered with coral; 2) the atama edged with a border of small stones; and 3) the inner space of the building (of which the outer area is reserved for the village people. Unimwane (old men) sit in their allotted boti and the central space is reserved for performances. The parts of the mwaneaba and the building process itself are spiritually, physically and symbolically of great social significance for both individuals and the village.

The building process, as well as the final structure, provides a sense of individuality within a supportive and communal framework. The carefully staged building procedure, with its celebrations and regard for te tabunea of the master builder, are designed to provide ‘safety’ in the debate and decision making practices of te mwaneaba.

|

| No ladders or scaffolding is used, the men climb the poles and use string to lash the poles to each other |

After ones initial impression of the complexity and apparent randomness of posts and beams, a simple symmetry of construction emerges. The symmetry of right angle and 45 degree triangles is repeated everywhere - in the triangulations of the huge pandanus logs, the positioning of the coral supports, the all important boua ni kaua (vertical ridge poles) and the intricate knotted patterns formed in the lashings of te kora (string). A duality exists, that echoes the function of the mwaneaba itself, of elegant simplicity within a complex and enduring strength. The awe felt is closely associated with a reverence that reflects the investment of care and attention by the village in the mwaneaba construction and use.

|

| Performing Traditional Dance in a Mwaneaba |

The knowledge systems for building the traditional mwaneaba have been developed over centuries and reveal a profound understanding of sustainable construction techniques within the context and the resources of a coral atoll. Imported building materials have been less well-adapted to the I-Kiribati context. The thatched roof of the traditional mwaneaba provides cool shade even on the hottest of days; the floor comprises gravel and coarse hand-woven palm mats which are comfortable and dry to sit on. In contrast, the tin roofs of the urban mwaneaba heat up rapidly and produce uncomfortable temperatures within. The same roofs make speeches inaudible when it is raining. Concrete floors are uncomfortable to sit on for the often-lengthy proceedings within the maneaba.

Summary

In summary, te mwaneaba arises from, and influences, an integrated and holistic knowledge system developed within a fine balance of skill, material and place. It contributes to the maintenance of cultural practices and beliefs through its dominant presence in the community. Not only does the traditional mwaneaba serve a practical function as the site for important social matters, it is also a symbolic system for self- definition of both community and individual.

In the indigenous knowledge systems of Kiribati, which are grounded in the ‘here and now’ of subsistence living, the introduction of imported materials in the construction of the culture’s single most significant and important cultural artifact has a significant impact upon cultural knowledge, practice and, ultimately, and what it is to be I-Kiribati.

Many of the urban Tarawa youth have little or no experience of traditional mwaneaba protocol or authority. Their sense of self-definition is by association with the contemporary materials. The sense of common ownership through te mwaneaba construction is replaced by the more abstracted notions of cash donations or fund-raising for the church or school maneaba built of imported materials. The youth of Tarawa, though, enjoy the freedom within the urban mwaneaba.

**********************************************************************************************

Most of the information in this post is from an article by Tony Wincup; "TE MWANEABA NI KIRIBATI: The traditional Meeting House of Kiribati: A Tale of Two Islands" Shima: The International Journal of Research into Island Cultures. Volume 4 Number 1 2010 - pg 13-30